Fighting Is Art

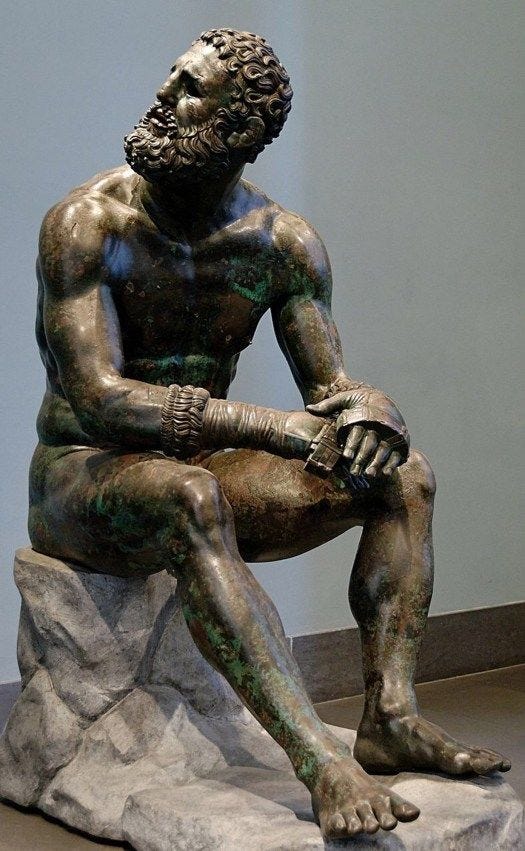

What first comes to mind when you hear the word art? Likely the high arts; painting, music, sculpture, writing, and dance. Things which have built cultures and persisted for hundreds of years. These things are rightly valorized as their beauty is able to evoke powerful emotions in an individual. Boxer at Rest, The Ninth Wave, Among the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Battle, It’s a Wonderful Life, Singin’ in the Rain, One Piece, GTO, The Lord of Rings, The College Dropout, Closer to Home (I’m Your Captain), Acid Rap, Clair de Lune: these are some of my favorite pieces of art which evoke hope, glory, wistfulness, power, laughter, and love. Art is capable of changing peoples’ lives for the better. It is why great art is talked about for hundreds, even thousands of years.

Fighting is the same. There are those with the opinion that fight sport is low-brow, crass, and vulgar. They are right in the sense that the violent nature of the combat arts have a low-brow appeal. The mistake is made in thinking that this is the only aspect involved, and that a fascination with violence is somehow dirty or wrong. The propensity for violence is something ingrained in human nature. War and conquest are a staple of human history. Violence is fundamental to the human experience. Instead of trying to Puritanically scrub it away, there is value to be extracted from the art of fighting.

What exactly is art? Recently I heard it described as messages from heaven, or the ether, that can be received to transmute into reality. Great artists are those in tune with receiving such signals who do not allow their pre-conceived notions, ego, or fear block this pipeline from abstract to physical. Are great fighters not the same?

Training camps are meant to solidify certain habits in a fighter’s body. Habits that either shore up lingering weaknesses or take advantage of the opponent’s own tendencies. What a fighter does in the cage can be slowly baked in over a training camp, but what is left when a fighter is fatigued, hurt, or being controlled? Their natural tendencies. At a base level the fighter is an artist who has never changed. They have a foundation of skills they have always and will always use. In some fights you will see a fighter attempt new things for one round, and then revert to what they usually do by the second or third. Those whose natural ability for violence might be high in a domain, but who are ultimately unadaptable.

The best martial artists are those who can receive these messages both throughout camp and during a fight. They seamlessly build them atop their natural foundation. Jose Aldo had different looks for each of his opponents. Volkanovski started as a top player, transitioned into a skilled striker, and eventually blended these two styles into one cohesive game. Charles Oliveira became more confident as a result of his losses, building him a never say die attitude where he would have crumbled before. Though every fighter has a foundation the best are able to build upon it and become something new, something greater.

What can we learn about the artist as they create? A fighter’s style is a reflection of their temperament and approach to life. Khabib’s relentless pace was born from a commitment of attaining glory for God, drowning his opponent’s with pace until they succumbed. Charles Oliveira has a hellacious offense without regard for defense, trusting in himself, his journey, and God to carry him forward. Edson Barboza is a hammer, a destroyer who tends to wilt under the pressure of fighters not dissuaded by his bombastic offense. A style reveals the fighter’s psyche. Their movements are the physical manifestation of themselves, represented either pure as the message from the unknown, or tainted by human doubt.

Fighting is simply another form of self-expression. A human’s ability, temperament, passions, and experiences are made physical. One might relate to the bittersweet sorrow when listening to Clair de Lune, and the same when seeing Alexander Volkanovski get head kicked by Islam Makhachev.

Fighting can be seen as most similar to dance, given it is a bodily interpretation of the artist’s own emotions and heavenly messages. The sport of fighting is not so simple. The combat arts blends the character writing of a story, the plot of a film, the sculpted body of an athlete bred for combat, among others.

What’s behind a strike? Did he plan that or did he think of that in the moment? Why did he crumble under the pressure? How did he survive that onslaught? Are their children watching this? How in God’s name did he accomplish that? When watching a truly great fight any number of questions and emotions will overtake you.

While fight analysts can enjoy a fight from a tactical and technical approach, fights are made special because there is a story behind them. Many observers do not care about the actual strikes being thrown. They are impressed surely, but what is behind the fighter’s actions? Promoters have always sold combat sports as a story; the combatants should usually be fighting for a reason other than merit. Be it differences in ideology, race, blood feuds, or just pure hate, promoter’s look to sell the public something extra besides pure meritocracy. This can be bloviated but the most memorable fights throughout history are those that had heated buildups where the fight itself was simply the climax to a story that had been written.

In Sugar Ray Leonard vs. Roberto Duran I, Duran played the role of a villain by foul-mouthing Leonard’s will and wife, born from a belief that Leonard was given everything and had it easy. Leonard was the golden boy; incredibly talented, attractive, Olympic gold medal winner. He was the star while Duran was seen as the brutal workman from Latin America.

With that backdrop who would not want to watch the fight? The fight itself was beautiful where Leonard “fought against type” in an attempt to “brawl” with Duran. Attributed to Duran’s successful attempts at getting under Leonard’s skin, Leonard’s decision to fight this way would not have meant as much without the context of the build up.

The written story of the fight includes the build up before the fight and the climax of the fight itself. Within the fight there is a much more subtle story being written. A story where the promoter’s story and the façade of a story is discarded. In the ring, the true fighter is shown and understood.

If you want to see a quick example of a fight with a story look no further than Charles Oliveira vs Michael Chandler. A five-round fight condensed into six-minutes. The swings in momentum and eventual comeback tell a story all its own even if one knows absolutely nothing about either of the fighters. The bloody dance between the two fighters exhibits pain, intention, overcoming, and weakness. When you see Charles Oliveira end the first getting beat up and then start the second by throwing one of the most beautiful strikes of all time, you cannot helped but be moved by the indomitable human spirit.

The thrill of seeing a fighter overcome adversity unlocks that deep, intensely human piece of our soul, the one that knows the human spirit can push us past our limits and bring us closer to God. The disgust at seeing a brutal knockout conjures up awe at the ability of a human to devastate and horror at the state of another man. The strength of emotions that a fight, even moments of a fight can conjure up, are second to none. It appeals to our violent base nature and at its best calls to the glory of humanity to overcome all that stands in our way. It is why many movies are punctuated by a fight scene. Nothing is as exciting as a fight and little can express the human condition as raw.

What’s in a moment? A fight is a series of exciting moments stitched together to create an abstract story. A story written by two people seeking to overcome the other, adapting to each other’s actions and raising questions to the other. It is a dance, a conversation, a painting being created, a story being told. Chris Weidman’s spinning back kick attempt against Luke Rockhold is often cited as a moment of ignorance that led to his downfall as the greatest Middleweight in the world. Weidman tried one ugly move that led to him getting beat up, lose his title, and never look like the same fighter since. A single move with all that weight.

We must also acknowledge the aesthetic beauty of technical violence. Art which is seen as the closest to godliness is often music. Music exists for itself. It does not have an expressed purpose. We don’t necessarily understand why we like it or how it can evoke such strong reactions, but it does. A punch has a purpose, as does any move in the combat arts. Every movement is to deal damage to an opponent, lead to dealing damage, or prevent damage from dealing dealt to oneself. Though important, and some of the most effective strikes are often the most beautiful, movements can be appreciated for themselves.

If we were to look at these from a purely analytical perspective they are effective. But take all that away. Look at the strike simply for the movement that it is. Doesn’t that make you feel something? Doesn’t watching that scene make you want to run through a wall, feel a sense of something greater? Can’t you feel just a touch of God when you see that? There is something THERE separated from our interpretation of it, separated from its intended use. The movement of a strike is a beautiful. The movement of a takedown is gorgeous. A well-crafted submission is awe-inspiring. There is love to be found in fighting.

The science of fighting is intriguing and we can learn from it, but the art of combat is not something we should forget just because we want to learn more. The combat arts are just as valid of an art as painting or music. All have something to contribute, something to evoke, and can truly change the lives of human being. The artist needs to be a craftsman but he should not give up the smock for the hammer. Hold both. A great fighter is both a craftsman and an artist. The best fighters create art when inside a cage or ring and often create the most beauty while creating together. Fighting is art. Be an artist.

-Kick

Disclaimer: The video clips included in this article are not owned by the author. They are included for educational purposes only to illustrate key moments in the fighter’s career and demonstrate aspects of mixed martial arts techniques and strategies. All rights to the video content belong to their respective owners.

Appendix:

Boxer at Rest, 330-50 BC. Rome

The Ninth Wave by Ivan Aivazovsky, 1850

Among the Sierra Nevada Mountains by Albert Bierstadt, 1868

Battle by Fen de Villiers