How to MMA: Transitional Work with Benson Henderson

An Under-Appreciated Great

Out of all the Lightweight Champions that have graced the UFC Octagon, perhaps none are less touted by the modern-day audience than Benson Henderson. With transcendent superstars Conor McGregor and Khabib Nurmagomedov, and wildly entertaining legends like Anthony Pettis, Charles Oliveira, and BJ Penn, it would be hard to cement one’s place in this pantheon of 155-ers. This is not helped by the fact that “Smooth” was notorious for close fights and split decisions throughout his UFC, (and current Bellator), run. However this is a man who made his WEC debut in 2009, winning the WEC title within the same year. He has been fighting top flight competition in whatever organization he is in for 14 years, coming out on top the majority of the time. If that doesn’t say “All Time Great”, then I don’t know what does.

Henderson’s reputation for close fights have led many to believe he is either boring or not worth watching. Watching his fights paints a different picture: Benson Henderson is one of the finest examples of transitional work in MMA. A strange, creative genius, Henderson excels in positions unique to MMA; ground and pound, cage wrestling and striking, interstitial attacking, and flowing effortlessly between striking and grappling attacks.

Henderson’s transitional work largely presents itself in two ways:

1. Transitioning between phases

Which involves striking into the clinch, into grappling sequences, and all of the permutations between these positions.

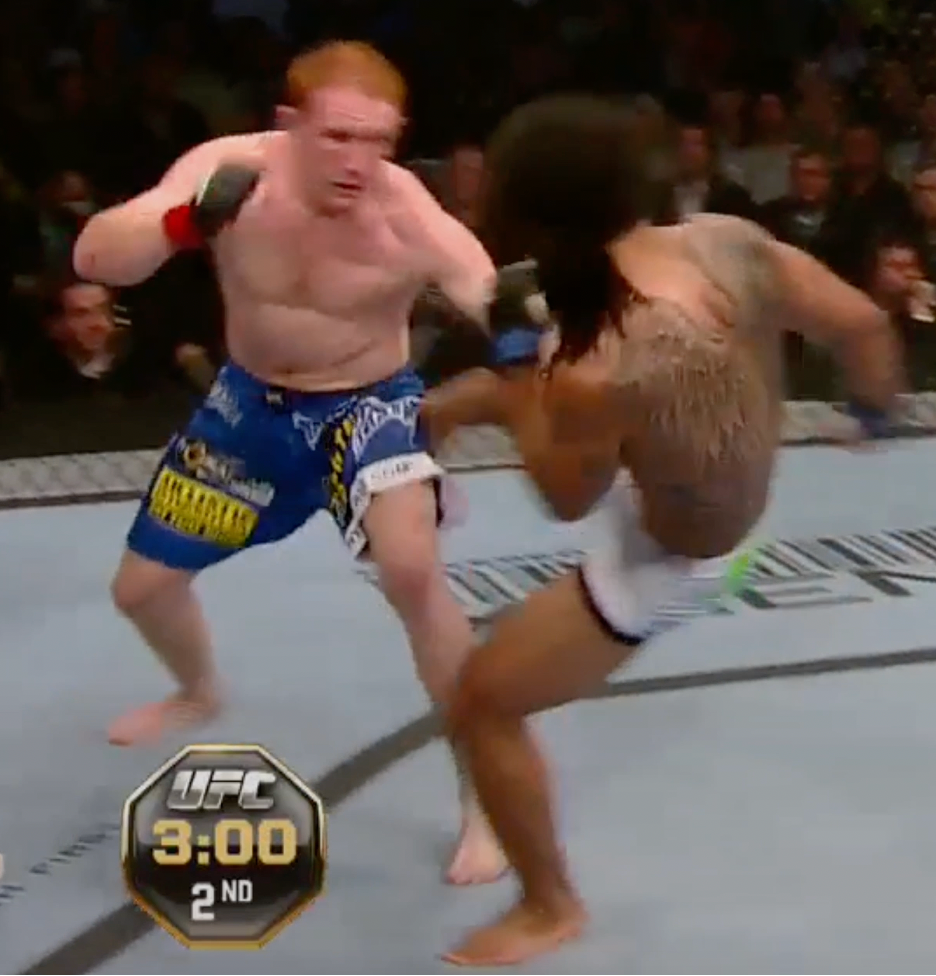

An example from his WEC title loss against Anthony Pettis:

1. Benson throws a leg kick . . .

Which throws Pettis off-balance

3. Henderson takes advantage of this by entering the clinch with a knee to the body

4. Which Benson follows by pressing Pettis up against the fence, controlling him and attempting to attack the back

2. Attacking during phase transitions

Attacking during these transitions involves striking or attempting submissions as the fight changes location from standing to ground.

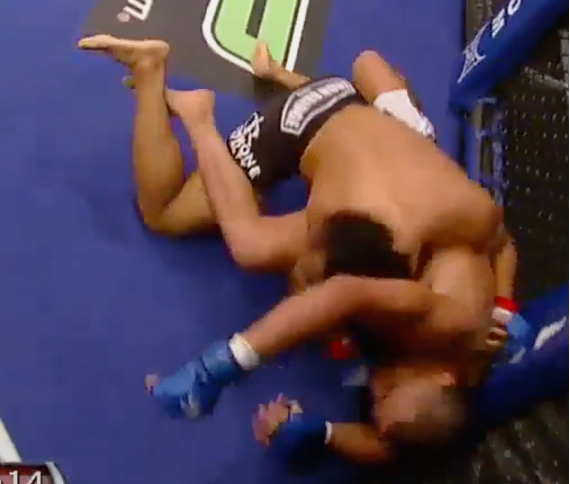

From his UFC debut against Mark Bocek:

1. Henderson throws a leg kick, which gets caught by Bocek

2. Henderson gets double under-hooks to defend the takedown

3. And he sprawls out to attack submissions from the front headlock

4. But Henderson does not chase the submission. Instead, he allows Bocek to stand-up, as he maintains double under-hooks, and stabs a knee into his midsection.

At his best, Henderson’s two-fold transitional work in better than most MMA practitioners even today and should be a case study on how to optimize fighting in a way unique to mixed martial arts. Some might say he’s even the best at . . . MIXING the martial arts. While not afraid to try new things (watch his title defense against Nate Diaz), he has a few favorite sequences that best exemplify his transitional work.

Striking Into Grappling

While a black-belt in Tae Kwon Doe, Benson’s most credentialed skill within the octagon is by far his wrestling. His scrambling is second to none, and rarely does Henderson get finished by a submission. The question is, how does he get the fight to the ground; to his realm? One method he shows is more typical of the modern MMA meta: pummel for under-hooks, hit the legs, body, and head with knees, and finish with a trip or high-crotch takedown. These portions of Henderson’s fights are admittedly more boring, but he succeeds in these exchanges with impressive regularity.

1. Henderson throws a knee to Pettis’ thigh with an over-under clinch

2. And he capitalizes upon this moment after to off-balance Pettis and attempt an inside trip

3. Finished with Pettis smushes against the fence by Henderson

Henderson’s other method of striking into grappling occurs in open space where his sequences of striking into takedowns grappling are both exciting and beautiful to watch.

Henderson throws a lunging rear hand straight

2. Using the momentum to drop into a single-leg takedown

3. Pettis is wise to it and sprawls. Henderson takes advantage of the reset after by throwing a body kick.

4. Shooting again as Pettis is against the fence

5. And is able to maintain control along the cage, despite not completing the shot

Pound Them Into The Ground

Henderson’s early WEC run was defined by wicked guillotines, which he would threaten throughout the rest of his career. This threat became an opening to find his way to top position, where he would begin his assaulting ground and pound. Reminiscent of Fedor in his prime, Benson did spectacular work aiming for an opening, switching targets between the head and body, and dropping elbows into the opponent’s face.

The main sequence to open the opponent up to strikes would usually involve:

1. A takedown into top position (shown here in his title defense against Nate Diaz)

2. Control the opponent’s legs and posturing up

3. To then throw straights to the body, wide swings to the head, and dropping elbows

Body

Head

Dropping Elbow

The damage from this positing was threatening and usually forced the opponent to turtle up, allowing Henderson to execute his next sequence of attacks:

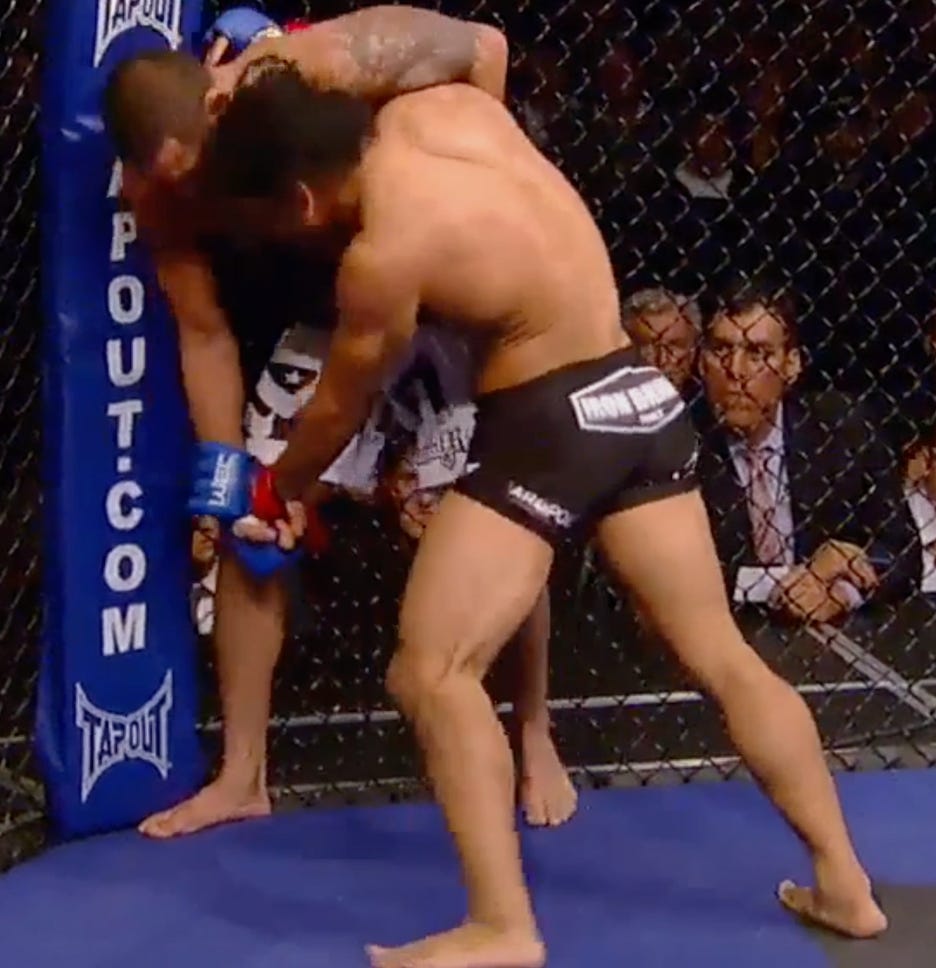

1. Threaten submissions from the front headlock (In his title winning performance against Frankie Edgar)

2. Use the submission threat to get to top position

Brutalize the opponent with strikes to the head and body

Continue to strike the opponent as they stand-up

This sequence was the most consistent way in which Henderson was able to do damage during grappling exchanges and force errors out of the opponent that he could then capitalize upon. His favorite method to punish an opponent off of a lazy stand-up? The head kick.

Ain’t That a Kick in the Head

Following Henderson’s suffocating attack sequences on the ground, the opponent had no option but to stand up. What they are not expecting is that Henderson is happy to let them do so in order to land the head kick. When it connects it is a devastating strike. Otherwise, it makes the opponent wary of standing up when on bottom (where he is at his most dangerous), stands them tall making them more susceptible to another takedown, and introduces danger to circling off from the cage.

Ex 1:

Benson has the front headlock against Clay Guida

He allows the standup while keeping a collar tie

In order to throw the knee to the body

And finish the sequence with head kick as Guida disengages and circles out (stabilized by a cheeky fence grab)

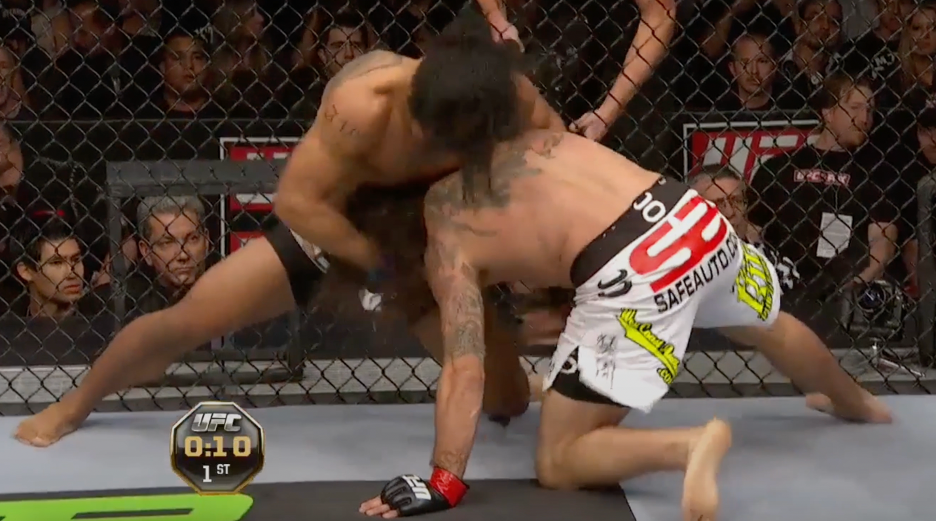

Ex 2:

Benson takes Diaz down with a double under-hook outside trip

And proceeds to brutalize Diaz with his patented ground and pound

Benson maintains enough control to continue striking as Diaz builds his base

Framing off his shoulders to measure distance and keep Diaz against the cage

To finally land a clean head kick as Nate regains his posture

Benson is able to do the same exact thing to Diaz at the end of round 5:

Brutalizing him from top position, and punishing the stand-up with a head kick

Ex 3 (Playing with expectations):

Henderson again brutalizes Diaz from top position

And frames off the head as Nate stands up, but Nate is aware of the head kick threat, and puts his arm back to stifle the path of the leg

Instead, Henderson attempts an outside trip. Unsuccessful, but incredibly clever thinking, playing with Diaz’s expectations mid-fight.

Striking into the clinch and takedowns, threatening between ground and pound and subs, and punishing the standup with a head kick form a potent system of attacks unique to MMA. Henderson’s transitional tools are something more fighters should be incorporating into their own kit. If one can learn to thrive here, they will have an enormous advantage over their competition.

Though he is nearly 40, Benson will be competing for the Bellator Lightweight Championship tomorrow night against Usman Nurmagomedov. I wish this absolute legend nothing but the best, and we will see if his frustrating and inventive style can neutralize the Dagestani game.